Wind, Fire, Water, Hail: What Is Going on In the Property Insurance Market and Why Does It Matter?

Published: December 14, 2023

Views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent official positions or policies of the OFR or Treasury.

The U.S. property and casualty (P&C) industry homeowners line has experienced poor financial performance in recent years with five of the last six years reporting underwriting losses.1 This adverse trend continued during the first half of 2023 despite the absence of the occurrence of a singularly large loss event such as a major hurricane.2 The most recent poor performance is largely due to the incurrence of a sizeable number of moderate-sized losses. Arthur Fliegelman explains these losses and examines how these challenges have economic impacts that stretch beyond insurers and their insureds.

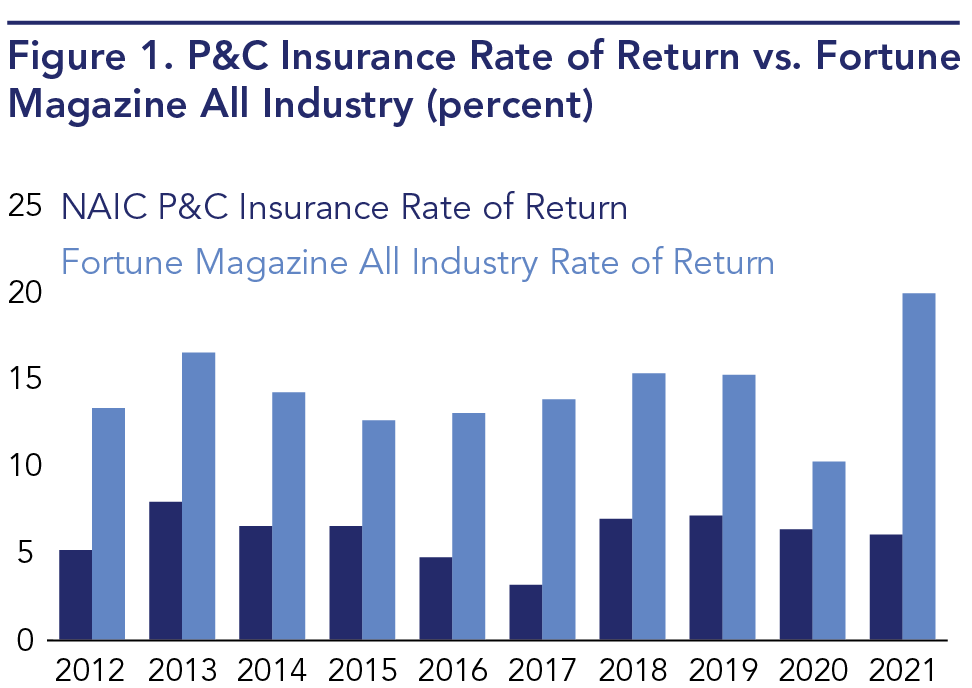

The P&C industry has historically financially underperformed the overall U.S. industrial and service sector, but in recent years, this performance gap has grown larger (see Figure 1). The property insurance sector is under heavy pressure from poor financial performance due to unexpectedly high inflation, a shift of exposures to higher-risk areas, and rising reinsurance costs. In addition, the insurance industry is incurring rapidly growing losses from modest sized but more frequent weather events such as severe convective storms resulting in large cumulative losses. These changes have resulted in the traditional insurance and reinsurance economic models becoming stressed and causing significant disruption in the traditional insurance operating model.

Insurance industry challenges impact property owners, property users, real estate lenders, including banks and government-sponsored enterprises such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and governments that collect property taxes since insurance cost and availability contribute to determining whether new property developments are economically feasible, where they can be built and their cost to build and operate. Seventy-seven percent of U.S. homes are financed with mortgages and are subject to insurance purchase requirements regardless of cost.3

Insurance coverage can be vital for rebuilding properties and communities after large disasters.4 However, some properties are uninsured or underinsured.5 A lack of insurance makes recovery for affected individuals and communities more difficult. The absence of adequate insurance coverage, such as in parts of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, could result in homeowners abandoning properties due to a lack of repair funds and may result in declining neighborhood property values.6

If the area damaged is sufficiently large, there could be macroeconomic effects and could negatively impact financial institutions exposed to a substantial number of affected properties.7

According to the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), increasing climate related losses and decreasing insurance coverage for these losses could increase financial institutions’ exposure to disaster risk including that of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and may have financial stability implications.8

According to research published by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), increasing climate risk protection gaps could pose a threat to financial stability to banks with large exposures to real estate-related catastrophe risks.9

Note: Return on net worth. P&C based on mean net worth and All Industry on year-end net worth. All Industry based on Industrial and Service sectors. This figure is provided by the NAIC and represents an approximation based on a simple average of Fortune’s Industrial and Service sectors.

Sources: NAIC, OFR

Spotlight on Florida’s Hurricanes and California’s Wildfires

The insurance markets in Florida and California have received the most attention from media, but property insurance market problems extend far beyond these two states. The Florida insurance market has been challenged ever since Hurricane Andrew in 1992 permanently changed the insurance industry’s appreciation of the potential large size of hurricane-related losses. The California insurance market was similarly shaken by unexpectedly large wildfire losses in 2017. Since these events, both insurance markets have become very different than previously.

Florida: Storms and Floods

Insured losses in Florida from storms and floods are covered by a combination of private insurers, a state operated insurer and reinsurer and the Federal government’s flood insurance program. Despite these programs, many losses remain uninsured or underinsured.

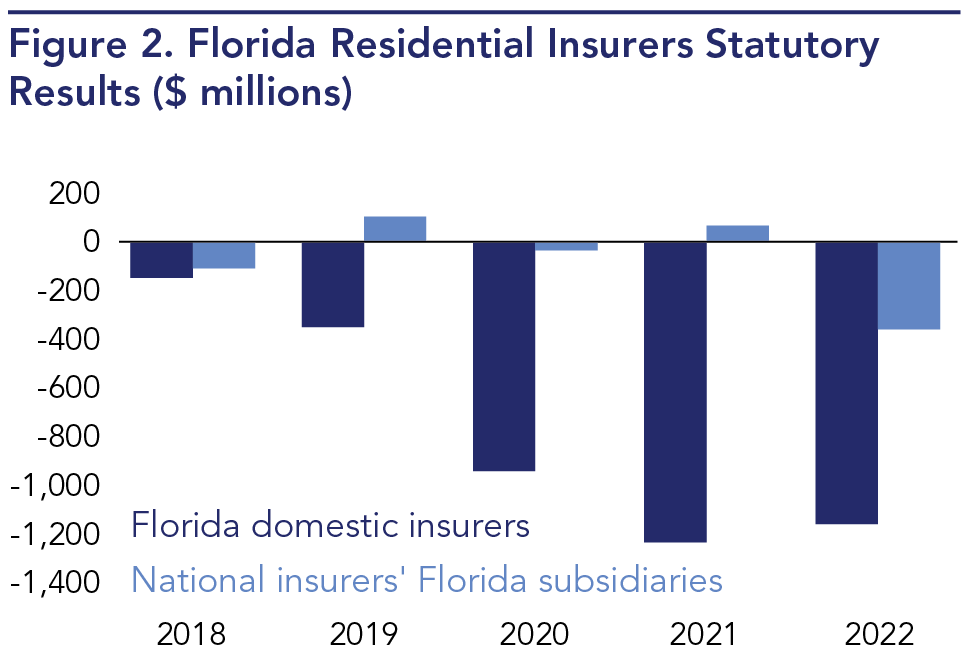

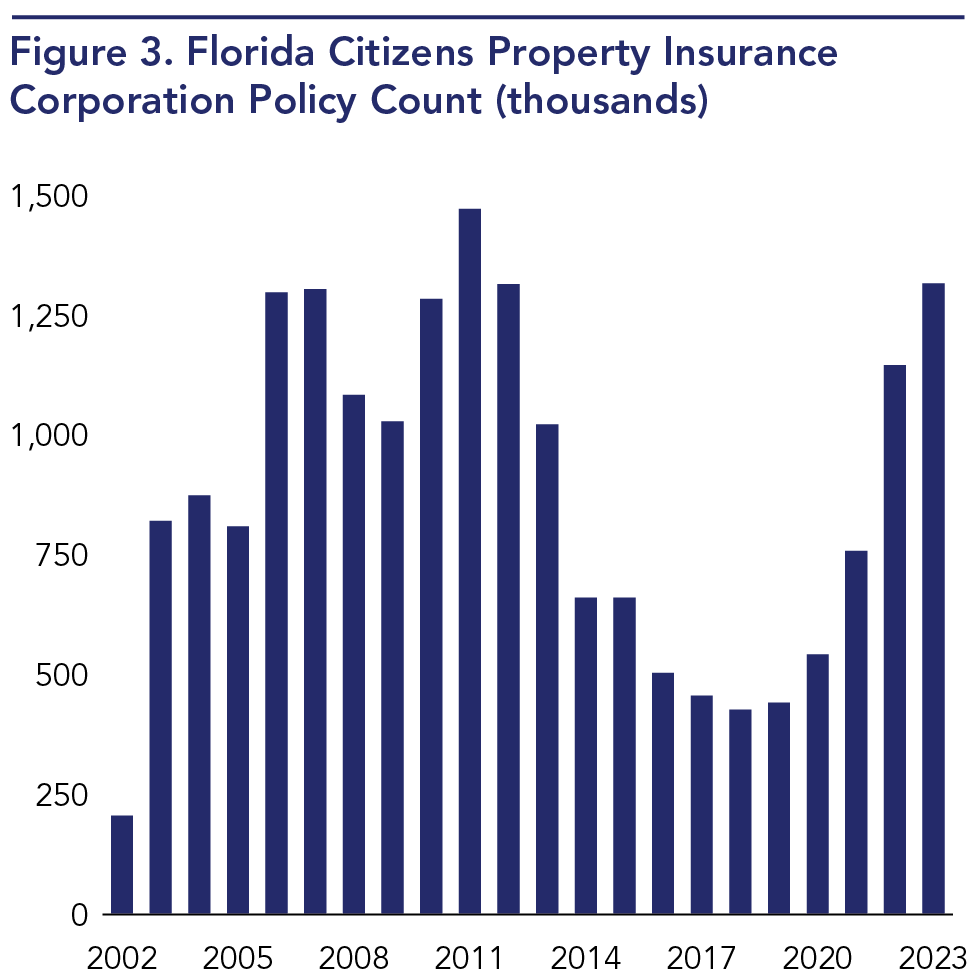

Nine Florida-focused P&C insurers have become insolvent since 2021. Other private insurers have voluntarily backed away from the Florida market due to the market’s poor financial performance (see Figure 2). In response, the state-operated Citizens Property Insurance Corporation (Citizens) has become increasingly vital to the Florida insurance and real estate markets as insureds have turned to Citizens for coverage (see Figure 3). Without Citizens, coverage would likely be impossible to get in parts of the state. Florida is also involved in the insurance market through recently enacted state-operated reinsurance programs.10

Note: Excludes Citizens Property Insurance Corporation

Sources: S&P Global Market Intelligence, OFR

Note: Policy count as of December 31 except for June 30, 2023.

Sources: Citizens Property Insurance Corporation, OFR

Despite the state’s involvement, many potential insureds still find it costly or difficult to get property insurance, especially in the highest-risk areas. Rising insurance costs and catastrophe-related losses can reduce property values and impede Florida’s economy.11 It is said that Florida is the riskiest property in the world for insurers to insure from a catastrophe risk perspective.12

According to the Insurance Information Institute, the average premium on a Florida homeowners’ policy is around $6,000 per year versus the U.S. average of $1,700 per year.13 In addition to homeowners’ premiums, Florida homeowners should carry a flood insurance premium at a substantial additional cost. They will be generally required to do so if they have a Citizens’ policy.

While Florida has passed several recent legal reforms to stabilize its market by addressing legal system abuse and misuse of assigned benefits, it remains to be seen if these changes will fully address those problems.14

California: Wildfire

Insurance availability in California has also recently become challenged due to the rapidly increasing severity of wildfire-related losses incurred by insurers. Numerous insurers are consequently declining to write new risks. In some cases, insurers are dropping existing coverages due to the rapid growth of this risk.15 Nineteen of California’s leading homeowners’ insurers have restricted writing coverage in the state to some manner, with some withdrawing entirely from the market.16 The California Association of Realtors reports that no private-sector insurance is available for prospective homeowners in some higher-risk areas.17

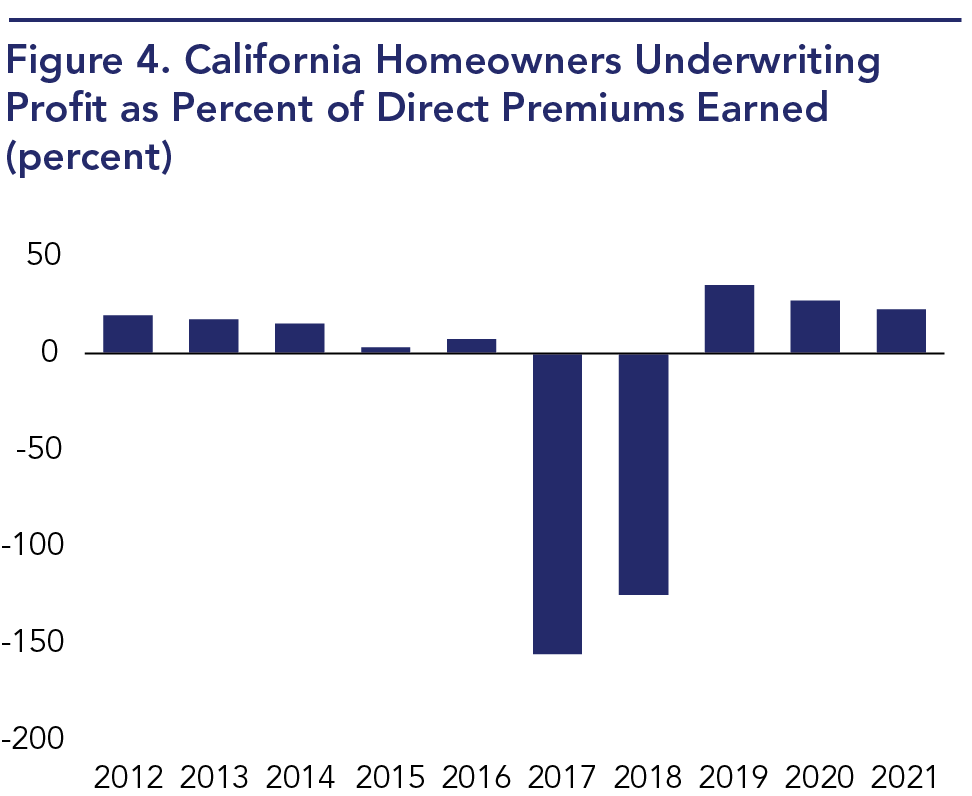

California has become subject to large wildfire losses as real estate development expands into higher-risk areas, repairing or replacing properties becomes more expensive, and climate change raises the number and scale of large fires. This has resulted in California insurers incurring large underwriting losses on their homeowner policies (see Figure 4). According to CoreLogic, more than 1.2 million California homes are at risk of wildfires.18 All five of the costliest U.S. wildfires have occurred in California, four since 2017.19

Uniquely, California law includes certain regulatory requirements related to the premium rate-setting process from Proposition 103. These requirements were not overly problematic when adopted, but with recent market changes, insurers now consider them a significant market impediment.

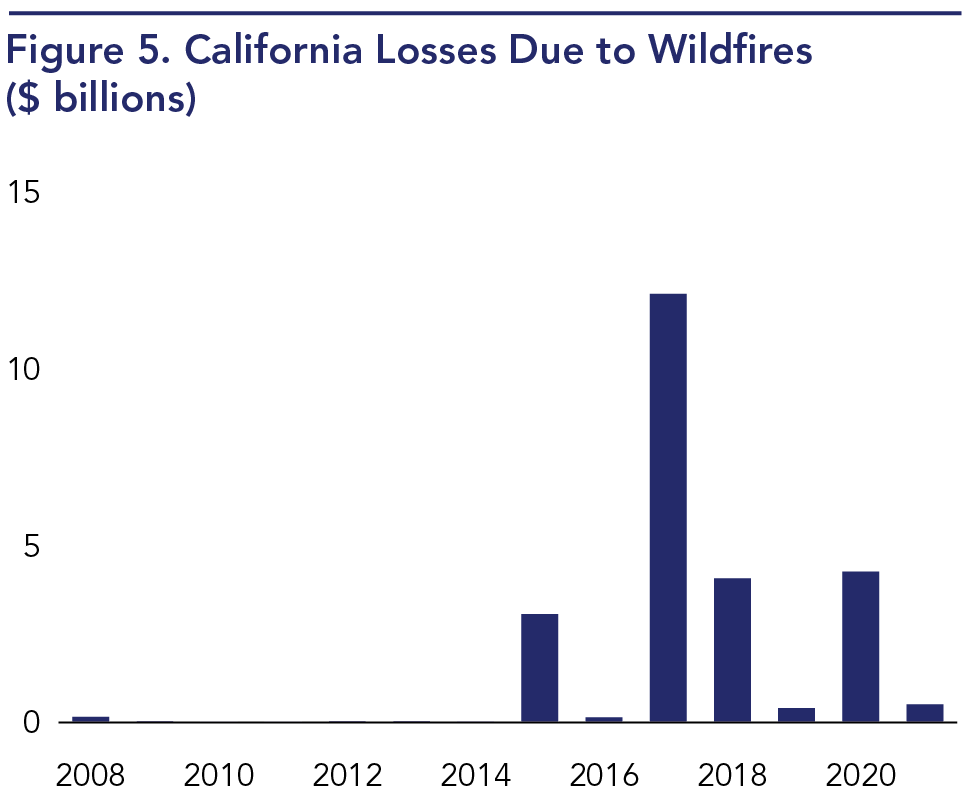

Three key Proposition 103 requirements are: (1) rate increases of more than 7% can be subject to a public hearing, extending the time process to get premium rate adjustments; (2) property insurance catastrophe premium loadings must be based on a minimum of 20 years of past claims history irrespective of the rapid recent growth of wildfire losses (see Figure 5); and (3) the lack of recognition of reinsurance costs as part of the rate-setting process.20

Note: Please see the Disclaimer page of the NAIC Report for detailed qualifications.

Sources: NAIC, OFR

Sources: CalFire, OFR

Without significant regulatory changes, insurers claim that it may be impossible for them to appropriately price California property insurance. California’s governor and Department of Insurance have recently announced plans to make changes to stabilize the state’s insurance market.21,22 These changes are still in preliminary stages. To date, these announcements have had no noticeable effect on opening the California insurance market. Historically these types of changes result in higher premiums, especially for the most risk-prone properties. In the meantime, insurance coverage in California remains hard to obtain, especially for properties at greatest wildfire risk. Over time, the unavailability, and rising cost of insurance will impact California real estate’s value, some of which is uninsurable in the private market.23

National Flood Insurance Program

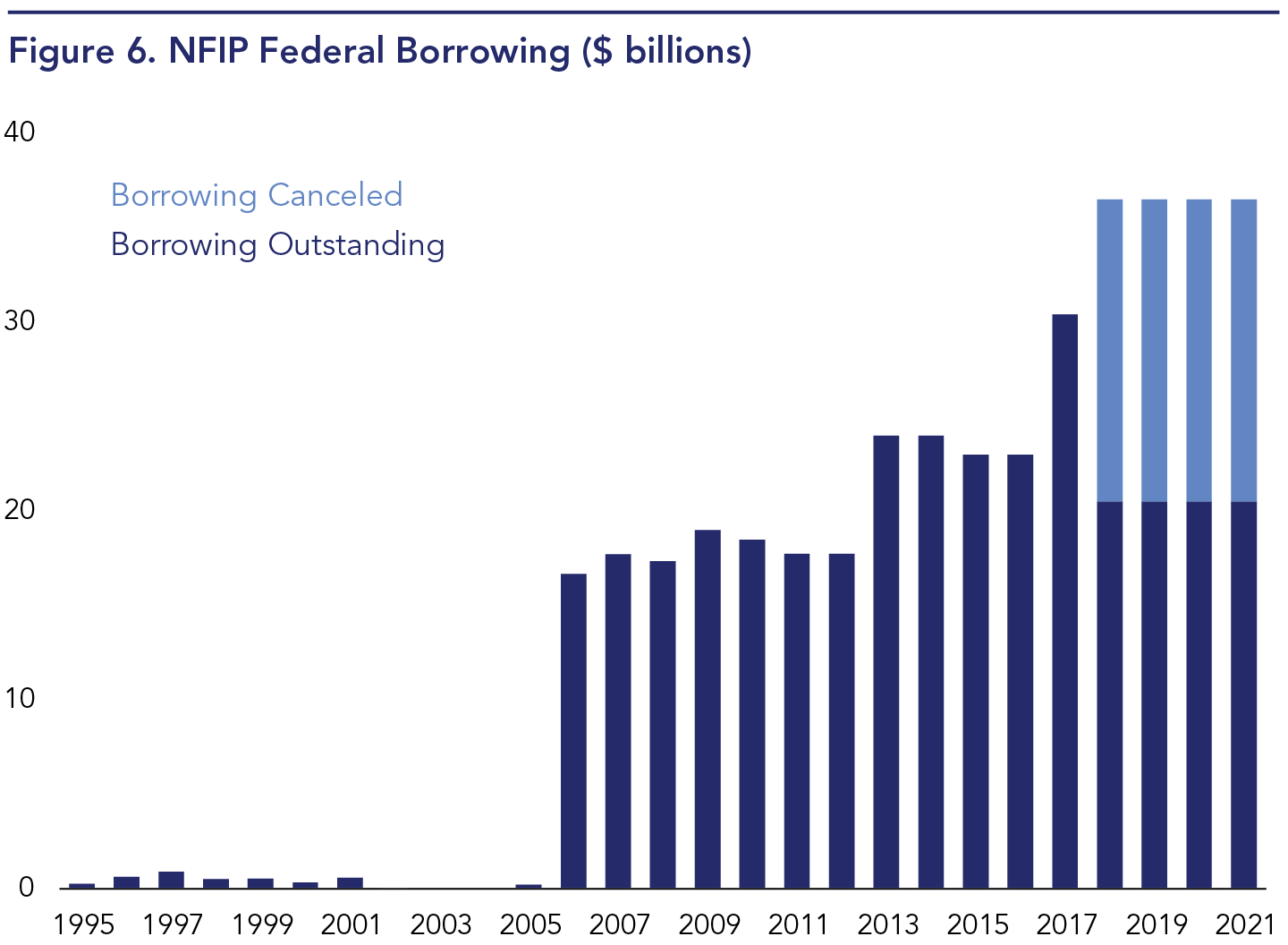

FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) began in 1968 due to the lack of a private flood insurance market. For years, the program operated with little public attention. Until 2005 and Hurricane Katrina, NFIP had little debt. However, since 2005, NFIP has regularly incurred operating losses whenever a major event occurs.

NFIP incurred its first large loss in 2005 from Hurricane Katrina, which devastated parts of the Gulf Coast, including New Orleans. Since 2005, NFIP has periodically been hit by additional large, incurred flood losses, usually from large offshore storms landing onshore in heavily populated areas. As a result, NFIP has been regularly incurring operating losses.

NFIP currently owes $20.5 billion to the U.S. Treasury that it has borrowed to pay claims. This amount excludes $16 billion in previous NFIP’s U.S. Treasury borrowings that were forgiven by Congress in 2018 (see Figure 6).24

Note: $16 billion in outstanding debt was canceled by Congress in 2018.

Sources: Congressional Research Service, OFR

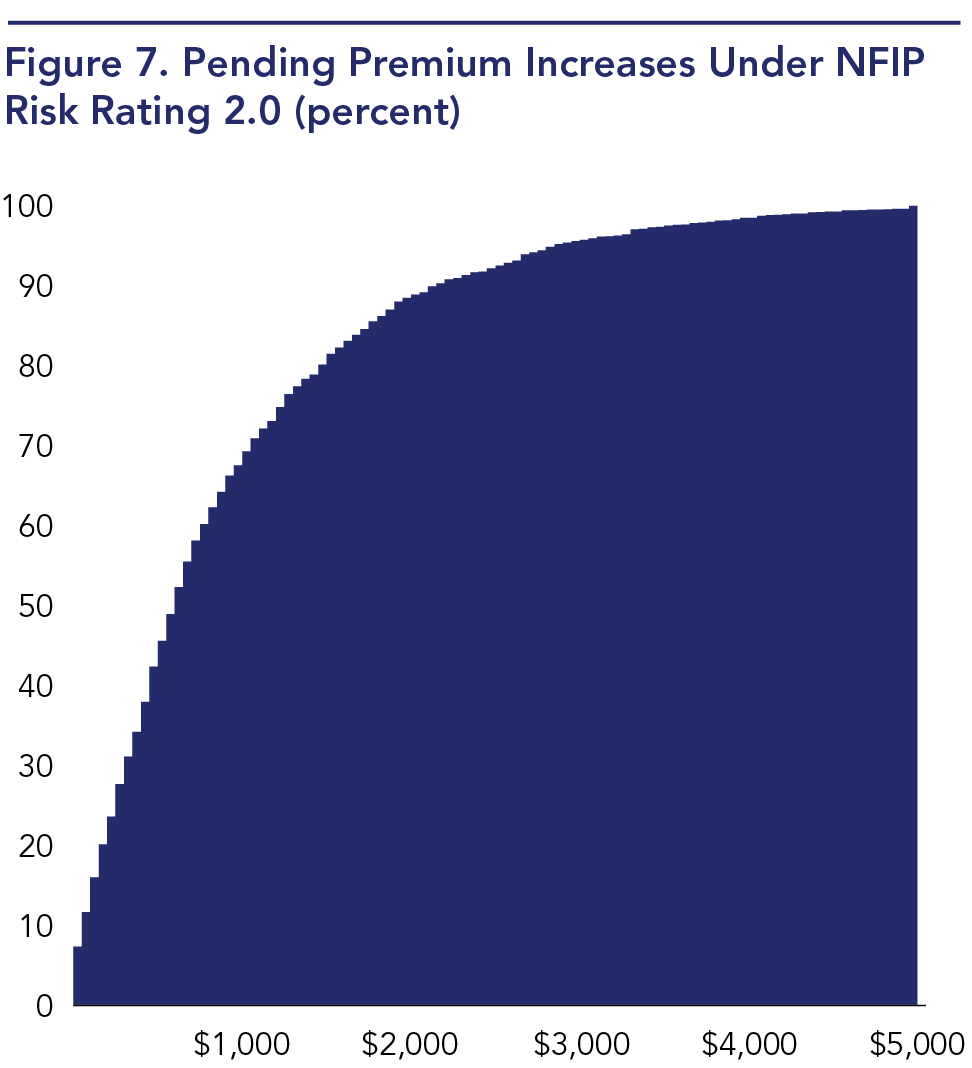

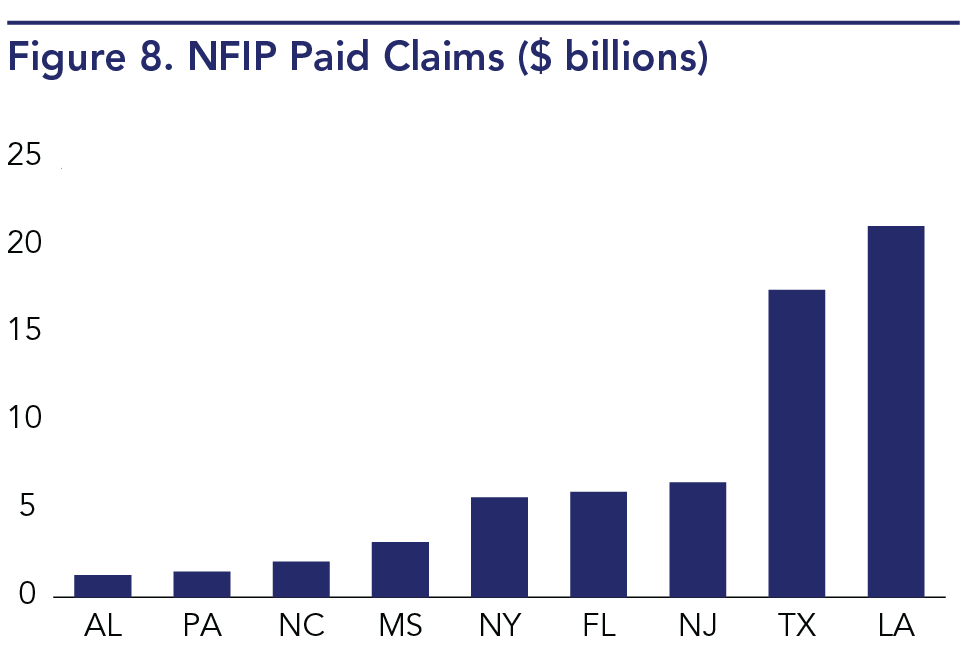

Under the NFIP’s recently adopted rating reform program (Risk Rating 2.0), NFIP is implementing a multi-year premium adjustment process intended to make NFIP self-sustaining (see Figure 7).25 However, these rate adjustments are subject to considerable opposition, including by members of Congress and a lawsuit by a group of states.26 It remains unclear if the NFIP will be able to fully implement its planned rating adjustments. While the NFIP has paid claims in every state, most claim payments are concentrated in a small number of states, especially Louisiana and Texas (See Figure 8).

Note: Cumulative distribution of planned premium increases to NFIP under RR2 to full risk-based rates.

Sources: FEMA, OFR

Note: Claims paid through August 2022. Claims paid in nominal dollars.

Sources: Open FEMA Dataset, OFR

The U.S. Government Accountability Office reports there is a fundamental conflict between two different program objectives: flood insurance affordability and the program being financially self-sustaining.27 The NFIP cannot accomplish both objectives simultaneously in its current framework even under Risk Rating 2.0. For example, repetitive loss properties, i.e., properties that have sustained multiple insured losses, make up 1.3% of all NFIP policies but account for 15-20% of NFIP claims.28 No private market insurer would voluntarily continue insuring such properties, but the NFIP must continue to do so. Congressional authorization for the NFIP’s operation expires on February 2, 2024, and it has not had a permanent reauthorization since September 30, 2017.29

Reinsurance

Insurance has traditionally managed the assumption of property risk largely by separating risk assumption into two discrete buckets. One is frequently occurring granular risks that can be readily assumed by direct insurers. The second are large, concentrated risks resulting in substantial losses too large for the direct insurer to assume on its own. Such large risks are shared globally through reinsurance. However, the reinsurance model has become increasingly challenged as the frequency and severity of large-scale losses have rapidly increased.

The reinsurance market, which serves as insurance for insurance companies, has been heavily impacted by the increasing frequency and severity of losses due to severe weather events, both in the U.S. and globally. In response, reinsurers have made major changes in their operations. This has, in turn, required primary insurers that rely upon reinsurance for risk transfer to make major changes in insuring homeowners and other clients from large-scale risks, especially in states such as California and Florida that are especially prone to such events.

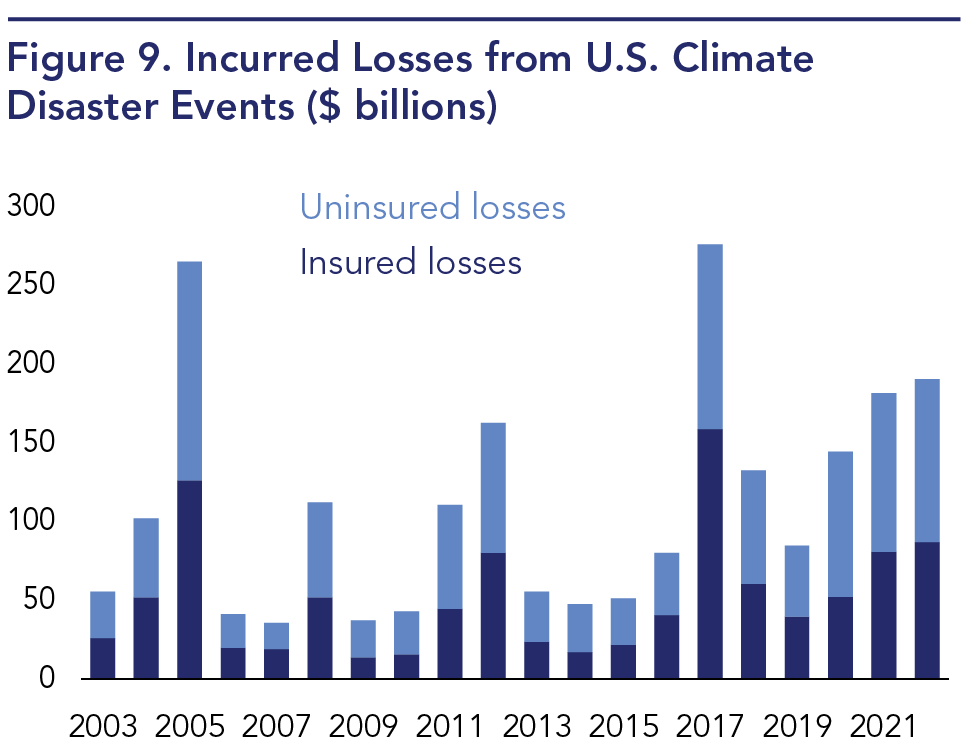

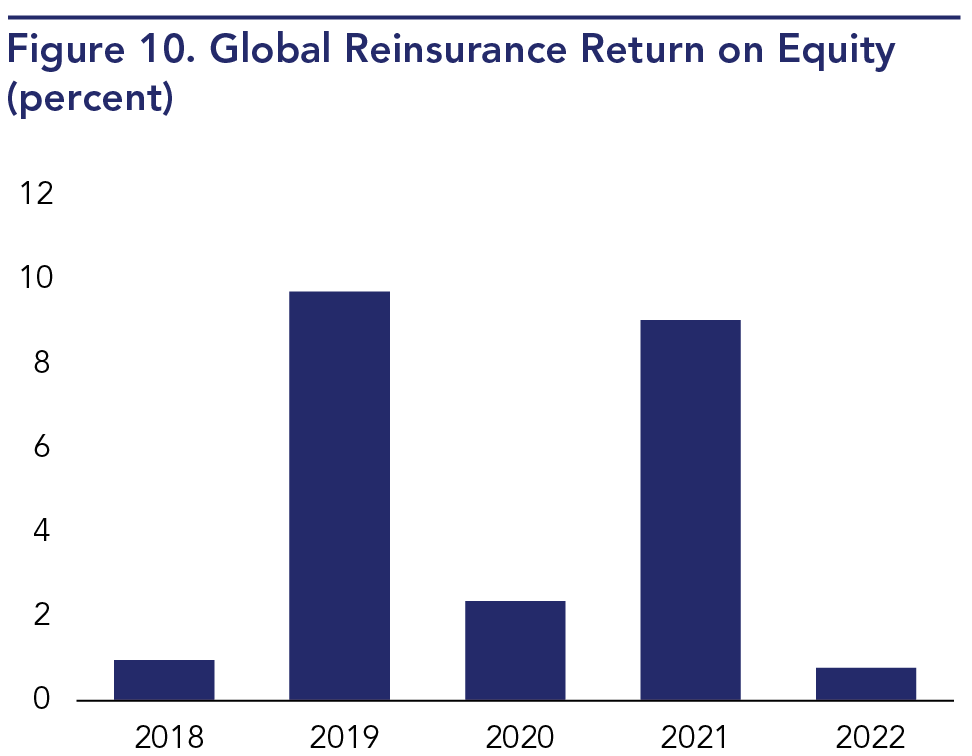

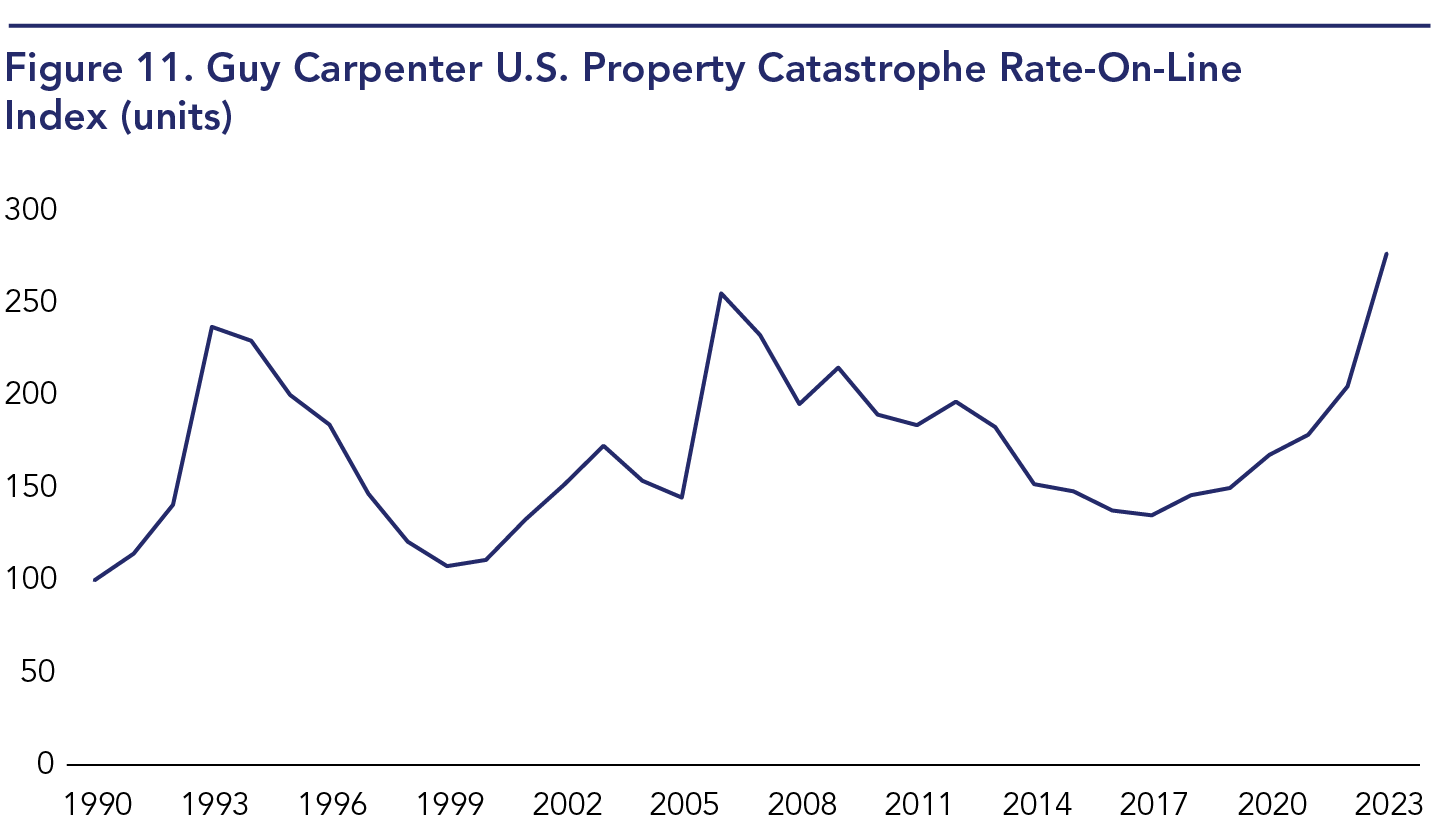

Reinsurance assists the primary insurer to meet its obligations after a major loss event. Reinsurance can be vital for smaller, less diversified insurers to keep the primary insurer operating after incurring a large loss. However, due to rapidly growing loss costs from major events, especially in the U.S., the financial performance of reinsurers has been poor for years (see Figure 9 and Figure 10).30 In response, reinsurers have made large premium increases, often well into double digits, and made numerous other contract changes to improve their financial performance (see Figure 11).31 Despite this, the availability of reinsurance remains limited. Limited reinsurance availability will hinder primary insurance availability, especially for higher-risk coverages where primary insurers often rely heavily on reinsurance.

Note: Losses in constant 2022 dollars. Disasters include tropical cyclones, severe thunderstorms, flooding, wildfires, drought and winter weather.

Sources: Gallagher Re, OFR

Sources: A. M. Best, OFR

Note: 2023 is as of July 2023.

Sources: Guy Carpenter, a business of Marsh McLennan, OFR

Conclusion

As insurance market developments continue, it is becoming increasingly challenging for real estate owners, users and related parties to protect themselves from the financial impact of adverse weather events via insurance. Whether it be a property owner subject to declining property values, a lender with a diminished loan collateral value, or governments with declining taxing ability, the financial risk from such events will become ever more important in the coming years. Parts of the market have become sufficiently challenged that some properties are now reported uninsurable.32

Insufficient insurance coverage, whether from floods, storms, wildfires, or other perils, leave property owners, lenders, and other parties at risk. Not all potential economic losses are insurable, but even those that should be insurable may be uninsured or inadequately insured because the property owner is unable or unwilling to pay requested premiums or the insurance is unavailable in the marketplace.

When uncompensated losses are sufficiently large, they threaten property owners’ and lenders’ financial solvency, the ability of local governments to provide needed services, and the economic vitality of an impacted region.33 Louisiana population declines and difficulty in undertaking financially feasible real estate developments are a reflection of the impact of multiple recent adverse weather events and could foreshadow what might happen more broadly as climate-related losses mount and insurance costs rise.34 If such developments become sufficiently widespread, they may result in national-level economic effects.

The recently issued Financial Stability Oversight Council report, “Climate-related Financial Risk: 2023 Staff Progress Report,” discussed how climate-related events can cause property damage, which reduces the value of real estate, negatively affects insurance profitability and the cost and availability of insurance and can spill over to the broader economy and the financial system.35

The First Street Foundation reports that 6.8 million properties have already been subject to increasing insurance rates, cancelled policies and reduced property values due to the rising ownership costs.36 Both the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) and the Federal Insurance Office are in the midst of efforts to collect more granular data on changes in the availability and cost of property insurance, especially in higher risk areas, in an effort to better understand the scope of the problem and how it might be best addressed.37, 38

Rising insurance premiums are not the fundamental problem. Rising premiums should be viewed as a market-based reflection of rising loss costs. In the long run, insurance premium growth can be constrained only when the underlying loss-causing fundamentals are addressed. There are no easy solutions.

Care must be taken that changes made in managing these risks and the insurance market be carefully thought out and not be subject to their own adverse consequences.39 Responses could include state guaranty funds and residual markets, but most important of all, meaningful efforts to mitigate the risks and improve resiliency after catastrophic events.

Efforts to address this challenge must extend beyond the insurance sector and will take substantial time and effort to develop, agree upon and implement. The longer this takes, the more we will see the cost and availability problem spread throughout the broader economy.

-

Blades, David, Maurice Thomas, and Alexander Fischetti, “Homeowners Carrier Challenges Stress Operating Results,” September 26, 2023. https://www3.ambest.com/ambv/sales/bwpurchase.aspx?record_code=336072&altsrc= ↩

-

Munich Re, “Earthquakes, thunderstorms, floods: Natural disaster figures for the first half of 2023,” July 27, 2023. https://munichre.com/en/company/media-relations/media-information-and-corporate-news/media-information/2023/natural-disaster-figures-first-half-2023.html. ↩

-

Wake, John, “U.S. has third lowest percentage of households that own their homes without mortgages,” Forbes, March 31, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnwake/2023/03/31/us-has-3rd-lowest-percentage-of-households-that-own-their-homes-without-mortgages. ↩

-

Walls, Robert, Sophie Pesek and Leonard Shabman, “Flood insurance, resilience, and recovery from disasters: The Case of Eastern Kentucky, Resources.org, August 31, 2022. https://www.resources.org/common-resources/flood-insurance-resilience-and-recovery-from-disasters-the-case-of-eastern-kentucky/. ↩

-

Insurance Information Institute, “Homeowners perception of weather risk: 2023Q2 consumer survey,” June 20, 2023. https://www.iii.org/sites/default/files/docs/pdf/2023_q2_ho_perception_of_weather_risks.pdf. ↩

-

U.S. Department of the Treasury, “The impact of climate change on American household finances,” September 29, 2023. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Climate_Change_Household_Finances.pdf. ↩

-

Kousky, Carolyn, “Informing climate adaptation: A review of the economic costs of natural disasters,” Energy Economics, November 2014. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140988313002247. ↩

-

Financial Stability Oversight Council, “Financial Stability Oversight Council Annual Report 2023,” December 14, 2023. https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-markets-financial-institutions-and-fiscal-service/fsoc/studies-and-reports/annual-reports ↩

-

Khoo, Felicia and Jeffrey Yong, “Too hot to insure – avoiding the insurability tipping point,” Bank for International Settlements, November 2023. https://www.bis.org/fsi/publ/insights54.pdf ↩

-

Roher, Gary, “Lawmakers plan $1B for reinsurance to stabilize property insurance industry,” Florida Politics, December 1, 2022. https://floridapolitics.com/archives/575542-lawmakers-plan-1b-for-reinsurance-to-stabilize-property-insurance-industry/. ↩

-

State of Louisiana, et. al. vs. Alejandro Mayorkas, et. al. Complaint, U.S. District Court of Louisiana, Docket No. 2:23-cv-01839, June 1, 2023. {Paragraph 225} https://climatecasechart.com/case/louisiana-v-mayorkas/ ↩

-

Rozsa, Lori and Erica Werner, Washington Post. “Florida’s Insurance woes could make Ian’s economic wrath even worse,” September 30, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2022/09/30/ian-florida-economy-insurance. ↩

-

Martinez, Marli, “More Florida homeowners are self-insuring amid rising insurance costs, survey says,” WESH, September 18, 2023. https://www.wesh.com/article/florida-rising-insurance-costs/45161582. ↩

-

Insurance Information Institute, “Trends and Insights: Addressing Florida’s Property/Casualty Insurance Crisis,” February 2023. https://www.iii.org/sites/default/files/docs/pdf/triple-i_trends_and_insights_florida_pc_02152023.pdf. ↩

-

Freeman, Andrew and Nathan Borney, “Uninsurable America: Climate change hits the insurance industry,” Axios, June 6, 2023. https://www.axios.com/2023/06/06/climate-change-homeowners-insurance-state-farm-california-florida. ↩

-

Zawacki, Tim, “Berkshire unit to exit increasingly embattled Calif. homeowners’ market,“ S&P Market Intelligence, August 3, 2023. https://www.capitaliq.spglobal.com/apisv3/spg-webplatform-core/news/article?id=76840049. ↩

-

California Association of Realtors, “State Farm, Allstate stop selling home insurance to new customers in CA,” June 1, 2023. https://www.car.org/aboutus/mediacenter/news/statefarm. ↩

-

CoreLogic, “Key insights into the new wildfire risk assessment for California property owners,” February 10, 2023. https://www.corelogic.com/intelligence/key-insights-into-the-new-wildfire-risk-assessment-for-california-property-owners/. ↩

-

Martin, Shanon, “U.S. wildfire statistics”, Bankrate, June 12, 2023. https://www.bankrate.com/insurance/homeowners-insurance/wildfire-statistics/. ↩

-

Timothy Daragh, “APCIA: Prop. 103 contributes to State Farm’s California property insurance freeze,” A.M. Best, May 30, 2023. https://news.ambest.com/newscontent.aspx?refnum=249980&altsrc=23. ↩

-

Executive Department, State of California, Executive Order N-13-23, September 21, 2023. https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/9.21.23-Homeowners-Insurance-EO.pdf. ↩

-

Lara, Ricardo, “Commissioner Lara announces Sustainable Insurance Strategy to improve state’s market conditions for consumers,” September 21, 2023. https://www.insurance.ca.gov/0400-news/0100-press-releases/2023/release051-2023.cfm. ↩

-

First Street Foundation, “The 9th National Risk Assessment: The insurance issue,” September 20, 2023. https://report.firststreet.org/9th-National-Risk-Assessment-The-Insurance-Issue.pdf ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency, ”NFIP Debt”, accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.fema.gov/case-study/nfip-debt#:~:text=Since%20Hurricane%20Katrina%20devastated%20the,in%20interest%20on%20that%20debt. ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency, ”Risk Rating 2.0: Equity in action,” accessed August 21, 2023. https://agents.floodsmart.gov/agents-guide/risk-rating. ↩

-

Florida Office of Attorney General, “Attorney General Moody fights FEMA to lower flood insurance rates for Floridians,” June 6, 2023. https://www.myfloridalegal.com/newsrelease/attorney-general-moody-fights-fema-lower-flood-insurance-rates-floridians. ↩

-

U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Flood insurance: FEMA’s new rate-setting methodology improves actuarial soundness, but highlights need for broader program reform,” July 31, 2023. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105977. ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency, ”Repetitive loss properties and the CRS,” accessed August 21, 2023. https://scdhec.gov/sites/default/files/docs/HomeAndEnvironment/Docs/CoastalCRS/AtkinsGlobal%20Presentation.pdf. ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency, “Legislative proposals for the National Flood Insurance Program,” September 22, 2023. https://www.fema.gov/flood-insurance/rules-legislation/congressional-reauthorization/legislative-proposals. ↩

-

Attanasio, Richard and Christopher Draghi, “Market Segment Outlook: US Personal Lines,” A. M. Best, December 4, 2023. https://www3.ambest.com/ambv/sales/bwpurchase.aspx?record_code=338268 ↩

-

Carvalho-Neff, Laline, et. al., “Stable outlook as higher pricing restores more favorable risk and reward dynamic,” Moody’s Investors Service, September 5, 2023. https://www.moodys.com/research/Reinsurance-Global-Stable-outlook-as-higher-pricing-restores-more-favorable-Outlook--PBC_1376099 ↩

-

Freeman, Andrew and Nathan Borney, “Uninsurable America: Climate change hits the insurance industry,” Axios, June 6, 2023. https://www.axios.com/2023/06/06/climate-change-homeowners-insurance-state-farm-california-florida. ↩

-

Financial Stability Oversight Council, “2022 Annual Report of the Financial Stability Oversight Council,” December 16, 2022. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/261/FSOC2022AnnualReport.pdf. ↩

-

Kaufman, Leslie, “Climate change Is causing an insurance crisis in Louisiana,” Bloomberg, September 11, 2023. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-09-11/louisiana-insurance-market-in-crisis-from-climate-fueled-storms. ↩

-

Financial Stability Oversight Council, “Climate-related Financial Risk: 2023 Staff Progress Report,” July 28, 2023. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/261/FSOC-2023-Staff-Report-on-Climate.pdf. ↩

-

First Street Foundation, “The 9th National Risk Assessment: The insurance issue,” September 20, 2023. https://report.firststreet.org/9th-National-Risk-Assessment-The-Insurance-Issue.pdf. ↩

-

National Association of Insurance Commissioners, “NAIC to Issue Data Call to Help Regulators Better Understand Property Markets,” August 15, 2023. https://content.naic.org/article/naic-issue-data-call-help-regulators-better-understand-property-markets ↩

-

Federal Insurance Office. “Treasury’s Federal Insurance Office Advances First Insurer Data Call to Assess Climate-Related Financial Risk to Consumers,” November 1, 2023. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1867 ↩

-

Federal Insurance Office, “Insurance Supervision and Regulation of Climate-related Risks,” June 2023. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/FIO-June-2023-Insurance-Supervision-and-Regulation-of-Climate-Related-Risks.pdf. ↩